many ways to live a life

Alice Andrews, 2015

That issues of money, sex, power and racial difference are inseparable from one another. That the richness and complexity of theory should periodically break through the moats of academia and enter the public discourse via a kind of powerfully pleasurable language of pictures, words, sounds and structures. That empathy can change the world. That feminisms suggest many ways to live a life and that they continue to question the conventional arrangements of power and the clichés of binary oppositions.

Barbara Kruger, Repeat After Me

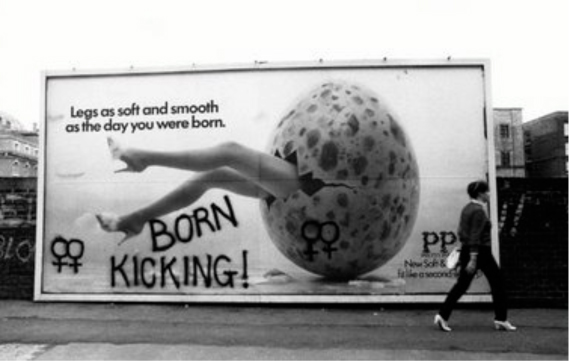

Feminist politics has had a fruitful relationship with the advertising billboard. The billboard has been the site of some of feminism's most visible contestation of patriarchal power in capitalist society. Some of the most ubiquitous and funny images of feminist action in public space, such as the graffiti and iconoclasm, most memorably documented by Jill Posener, have been found on the billboard. It has also been a tool used by feminist artists, most famously perhaps Barbara Kruger and the Guerrilla Girls, to take art and politics outside of the gallery and place it firmly in the public eye. In a society expertly practiced in the consumption of all things, including the reductive and inaccurate imagery of women offered by advertising and mass media, the subversion of the billboard still has a contemporary resonance.

Jill Posener, Born Kicking, graffiti found on a billboard in London, 1983. Copyright Jill Posener.

It is within this context that Thrive, Not Just Survive works. Helen de Main's most recent work for Bloc Projects, an artist-led project space in the centre of Sheffield, is a billboard showing images of women rarely seen in public media. The women on the billboard are all atypical billboard models: the smiling Muslim women riding a motorbike; the older animated activist; and a cheerful image of dancing women. These uninhibited images all transgress the boundaries put on women's bodies in public space. Whilst the diagrammatic structures that float in the background, imagined by de Main from models of shared collective information and action, physically map alternative definitions of power into the image.

Since the 1970s, various feminisms - radical feminism, intersectional feminism, poststructuralist feminism etc. - have sought to dismantle ideas and structures of power through a variety of methods, but all with an understanding that models of masculine power and domination, come at the expense of women.

Yet one feminist cause happily championed by the media is focused on women's access to equal levels of pay and positions of power – economic or political. Modern women we are told should strive to 'have it all' – to have work, family, money, property. In 2013, the quasi-feminist BBC Radio 4 programme Women's Hour put together its inaugural Power List populated and voted upon by listeners, which sought to find the UK's most powerful women. The resulting list which placed the Queen first, followed by Theresa May and Ana Botin, then CEO of Santander UK, and which also featured an entirely white top 20, illustrated just how mythic and misunderstood the notion of empowerment is in contemporary life.

De Main's interest in these feminist structures of shared power and knowledge, also, arise from her interest in the practices of second wave feminism, particularly around consciousness-raising. The practice of consciousness-raising involves the collective process of women exploring their lives, bodies and experiences with one another. Power, it is suggested by consciousness-raising, comes from the unsealing of one's body and the sharing of 'the personal' in order to help unlock individual and collective political potentials for women. Though some feminists have heavily critiqued these practices, most notably perhaps bell hooks, for their lack of revolutionary potential, their importance to understandings of feminist empowerment through the acknowledgement of 'the personal is political' is unquestionable.

In Repeat After Me, Barbara Kruger calls for a "powerfully pleasurable language of pictures, words, sounds and structures" – a statement that seems to resonate with de Main's own billboard. De Main's images offer up a pleasurable alternative to the conventions of representations of women in the mass media. That it seems so alien to see images of smiling Muslim women or older women dancing, that public displays of sisterhood, camaraderie and political action are so alien to how women are represented in public life, is expressed by de Main's insistence that these images should be seen. In an age where 'the personal is political' seems to have lost some of it's potency as a political maxim, the invasion of these images into public space illustrate that the personal and the political are still very much intertwined.

Short Bibliography

Barbara Kruger, "Repeat After Me" in Remote Control: Power, Cultures and the World of Appearances, MIT Press, 1994.

Jill Posener, Spray it Loud, Routledge, 1982.

Carol Hanisch, The Personal is Political, available online: http://www.carolhanisch.org/CHwritings/PersonalisPol.pdf

bell hooks, "Feminist Revolution: Development Through Struggle" in Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, South End Press, 1984. See also bell hooks, "Consciousness Raising: A Constant Change of Heart" in Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, South End Press, 2000 for a more positive exploration of consciousness-raising by hooks.

Alice Andrews is a feminist art historian working in Glasgow. This text was commissioned to accompany Thrive, Not Just Survive a new work for Bloc Billboard, by Helen de Main, 17 July – 16 August 2015.